For families moving from city water to a private well, one of the first surprises is how different water pressure feels. Municipal systems rely on large pumps and elevated water towers that maintain a steady 50 to 60 psi across neighborhoods. A private well, by contrast, is a self-contained system that depends entirely on your pump, tank, and the aquifer beneath your property.

When city water becomes well water, you no longer pay a monthly bill, but you also inherit full responsibility for pressure, yield, and maintenance. The question many suburban homeowners ask is simple: How can I increase water pressure and keep it consistent while protecting my well’s supply?

The good news is that steady, city-like pressure is possible with the right design, testing, and equipment.

City Water vs. Well Water: Why Pressure Feels Different

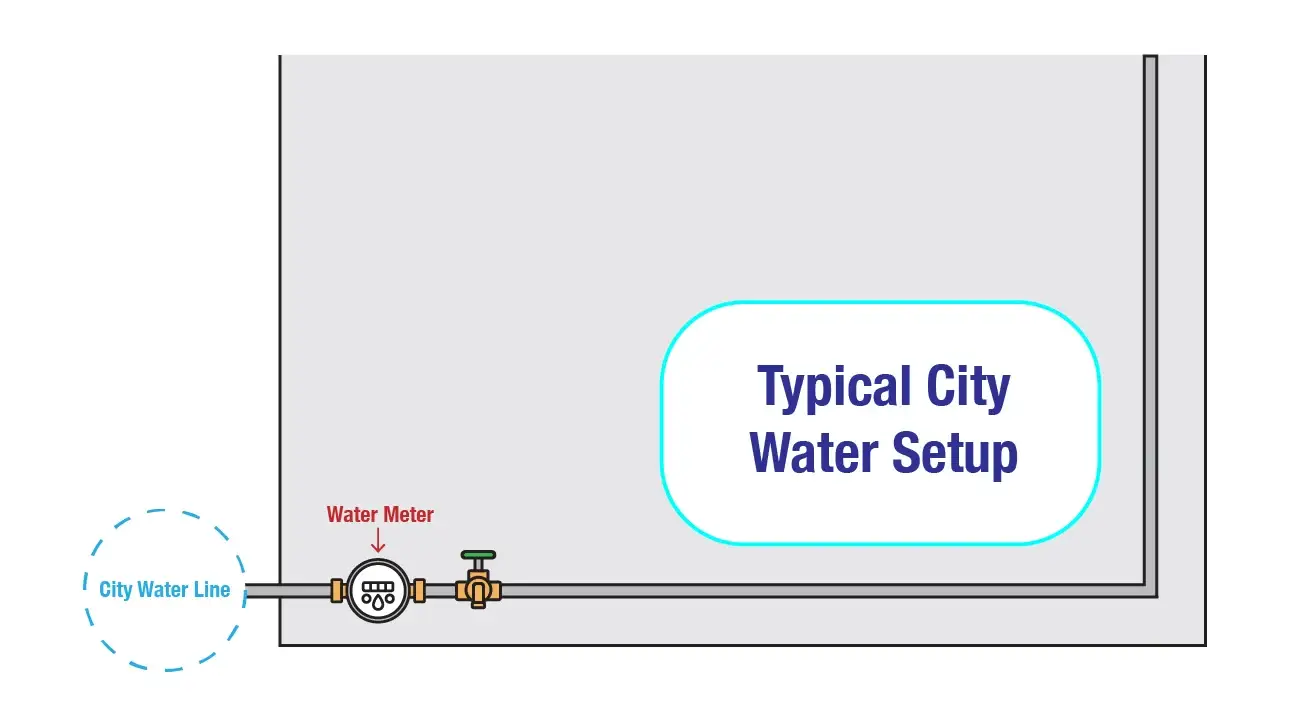

Public utilities pump water from surface or groundwater sources and deliver it through a network of pressurized pipes. The water you receive from the city has already been filtered, disinfected, and pressurized to meet drinking water standards. The Colorado State University Extension notes that most municipal systems hold a stable range of 50 to 60 psi, making low water pressure rare.

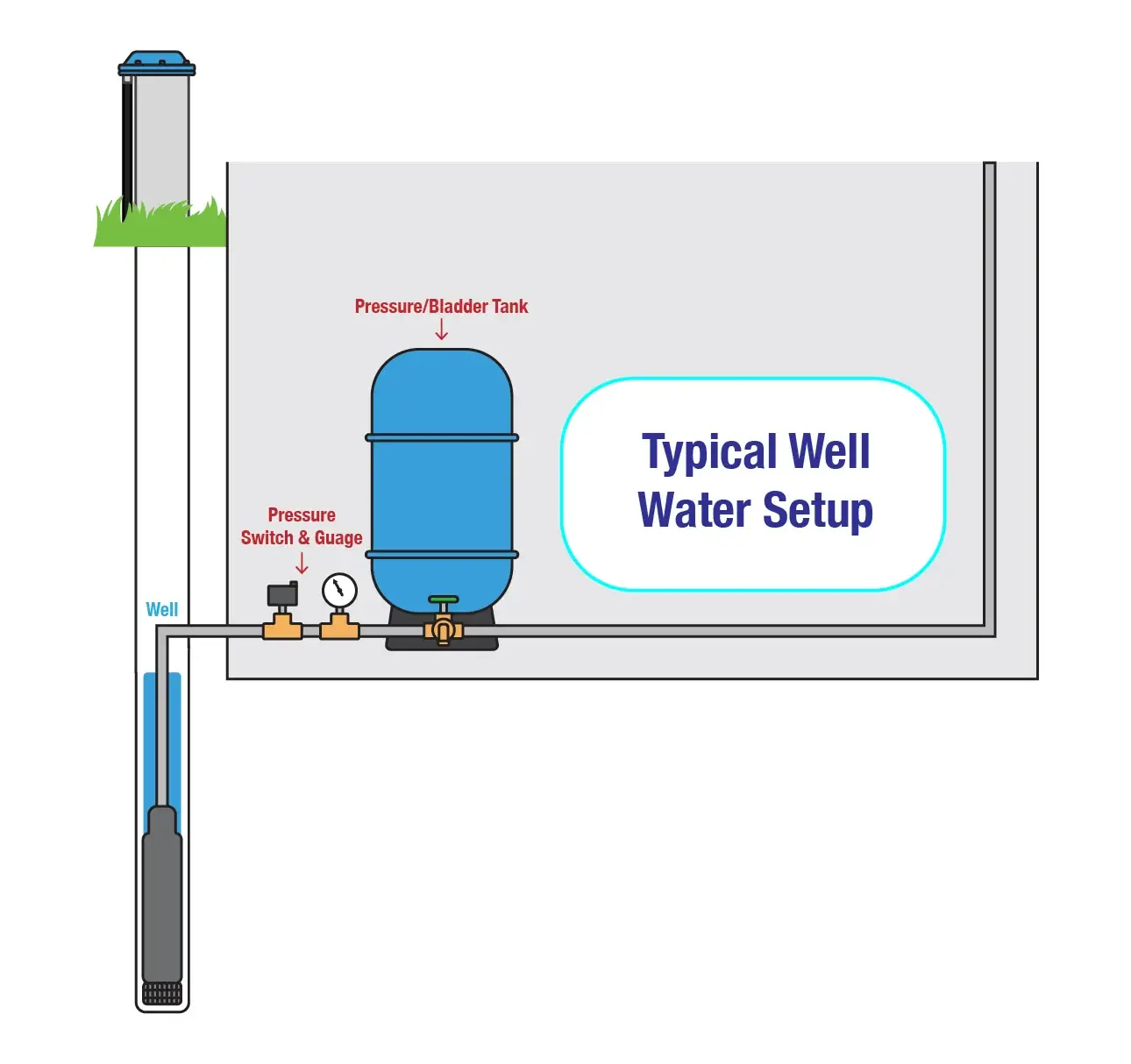

Private wells operate differently. The Alabama Cooperative Extension System explains that a residential well draws groundwater through a pump into a pressure tank, which feeds the household plumbing. The system has no external tower to maintain pressure. Instead, a switch turns the pump on at around 40 psi and off at 60 psi, producing the same pressure range that city water users are accustomed to, but only if the well can keep up.

The advantage of a well is independence. The tradeoff is that you must manage both the force (pressure) and the flow rate (yield) yourself.

Assessing Your Well’s Yield and Your Home’s Demand

Before worrying about how to increase water pressure, it helps to know what your well can actually produce. The University of Rhode Island recommends a professional yield test that pumps the well for several hours while measuring the change in water level. This determines the safe yield—the amount of water that can be drawn without lowering the level faster than the aquifer can recover.

Yields under three to five gallons per minute are considered low for a typical household. Penn State Extension offers a simple example: a family using 300 gallons in two hours will overdraw a one-gallon-per-minute well long before the morning routine ends. The solution is not always a new pump, but a smarter system that stores water and manages how it’s used.

To plan your setup, estimate peak demand by adding the water used for showers, toilets, laundry, and dishwashing during your busiest hours. If your total exceeds the well’s yield, you will need additional storage or lower consumption.

Equipment That Makes the Transition Work

A well system includes a submersible or jet pump, a pressure switch, a pressure tank, and often a water pressure booster with intermediate storage. Most pressure switches are set to start the pump at 40 psi and stop at 60 psi. That range delivers strong flow while protecting plumbing fixtures.

However, a pressure tank alone stores very little usable water. Penn State Extension notes that only about 20 percent of a tank’s volume is available before the pump must restart. This is why many new well owners experience low water pressure during heavy use, even when the tank seems large.

The fix is a cistern or storage tank between the well and the house. The well pump fills it slowly throughout the day, and a booster pump then supplies the home with steady pressure. The University of Arizona’s Cooperative Extension confirms that this arrangement reduces cycling, protects the pump, and provides constant flow that feels identical to city water. A good rule of thumb is to store at least 100 gallons per person.

Constant-pressure pumps with variable-speed motors are another option. They adjust pump speed to match demand, reducing wear and energy use, but they still require adequate storage to prevent short cycling. When properly installed, these systems make low water pressure a thing of the past.

Managing Pressure and Yield Every Day

Once your system is set up, maintaining consistent pressure becomes part of everyday care. Spread out high-water tasks like laundry and dishwashing instead of running them all at once. Install low-flow fixtures and modern appliances that can reduce water use by 25 to 30 percent without sacrificing comfort.

Check pipes, faucets, and outdoor spigots for leaks. Even small drips can make a pump cycle repeatedly, wasting power and wearing out components. Schedule water-intensive chores when your storage tank is full, and test your well water every year. The University of Arizona advises homeowners to protect the wellhead from contamination and maintain accurate records of pump age, pressure switch settings, and test results.

By combining small conservation habits with a well-designed system, you can enjoy consistent pressure without overtaxing your well.

Worked Example: From City Water to a Well

Consider a family moving from city water to a home with a private well that yields two gallons per minute. Their morning peak demand—showers, toilets, and laundry—requires about 400 gallons over two hours. The well can supply 240 gallons in that time, leaving a 160-gallon gap.

Following Penn State Extension’s storage guidelines, they install a 600-gallon cistern (100 gallons per person). The well fills the tank gradually throughout the day, and a variable-speed water pressure booster maintains a consistent 50 to 60 psi. By upgrading to high-efficiency showerheads and appliances, they cut peak demand to 300 gallons. Now, the well, storage, and booster work together to deliver strong, steady pressure, and the family enjoys water that feels exactly like the system they left behind.

Planning for Edge Cases and Special Conditions

Some suburban properties face placement limits or geological challenges. Wells must be set back from septic tanks, drain fields, and property lines, as required by state and county health codes. If your well produces less than one gallon per minute, or your aquifer is poor, storage alone may not meet demand.

Alabama Extension notes that deepening the well or lowering the pump can sometimes improve performance. Bedrock wells may also benefit from professional hydrofracturing, though results vary. Always consult a licensed contractor before attempting any modification, and check local regulations for required permits.

In coastal or contamination-prone areas, connecting to a small community system or supplementing with rainwater collection can provide extra security. The goal is to build resilience; enough stored water and steady pressure to handle both daily needs and dry seasons.

Bringing City-Like Pressure Home

Switching from city water to a private well means trading predictability for control. When managed correctly, that control is an advantage. You can decide how to increase water pressure, balance yield, and maintain independence without sacrificing performance.

The formula is straightforward: test your yield, size your storage correctly, add a booster system, and maintain everything on schedule. Those steps turn a private well into a private utility—efficient, steady, and ready for whatever your household needs.

At Well Manager, we specialize in helping homeowners make that transition as seamless as possible. Our systems combine storage, automation, and pressure management to deliver consistent, city-quality performance from private wells. If you’re facing low water pressure after moving off city water, we can help you build a system that keeps it strong for years to come.

Related Reading

- How to Increase Water Pressure in a Well System: Understanding Pressure and Yield

- Low Water Pressure Well: Why They Happen and How Well Manager Solves the Problem

- Why Does Well Water Pressure Drop When You’re Away?

- How to Increase Water Pressure When Standard Well Fixes Fall Short

- You Don’t Have to Live Like This: Fix Your Low Yield Well