Living on a private well often feels like independence until the yield number starts to bother you. Perhaps your driller informed you that the well produces only one or two gallons per minute. Perhaps you discovered the real yield during a dry spell when showers weakened and the pump ran for what felt like an eternity. On paper, that flow rate looks small. In daily life, it becomes a negotiation about who uses water and when.

Many low-yield wells still produce more than enough water over an entire day. The trouble is the way life uses water in short bursts. Mornings and evenings pile showers, laundry, dishes, and cooking into a few crowded hours. The well is not asked how much it can produce in twenty-four hours. It is asked whether it can keep up with the rush that happens in two.

A storage tank is a way to separate those two questions, allowing the well to work at its own pace and the home to maintain its own schedule.

What “Low-Yield” Means In Real Life

“Low-yield” sounds like a verdict until you look closely at what the well is actually doing. A slow well can still move a surprising amount of water across a full day. The real problem is that your life does not run across a full day. It runs in short bursts when everyone needs water at once.

Penn State Extension, in its guidance “Using Low-Yielding Wells,” notes that even a one-gallon-per-minute well can produce approximately 1,440 gallons in 24 hours if allowed to run steadily. The New York State Department of Health, in its fact sheet “Individual Water Supply Wells,” notes that wells producing between three and five gallons per minute typically have sufficient total water but may fall behind when multiple fixtures are used simultaneously. Below about five gallons per minute, they note that storage or careful flow control becomes more important to avoid constant low water pressure.

It helps to see the numbers side by side.

- 1 gallon per minute across a full day is about 1,440 gallons.

- 5 gallons per minute is still more than 700 gallons in a day.

- Many families use only 200 to 400 gallons per day.

On paper, the well can keep up. In practice, it struggles during the two or three busiest hours when showers, toilets, dishes, and laundry pile up on top of one another. The well is not failing as a source. It is failing as a direct, on-demand supplier.

A slow but steady well becomes stressful only when the home tries to live directly on that thin stream. A storage tank changes the relationship. It lets the well work quietly at its own pace while the household draws from a reserve that already exists when the morning rush arrives.

Clues That Your Well Is Falling Behind

You do not have to look at the well to know when it is struggling. The symptoms typically appear inside the house during ordinary daily routines. A storage tank is worth serious thought when patterns like these become familiar.

- Morning showers lose strength as soon as another fixture opens.

- The pressure gauge drops during busy times and creeps back up later.

- The pump runs for long stretches during peak hours, then barely runs at all overnight.

- Water is clear most days, but turns cloudy or sandy after heavy use.

Penn State Extension, in the fact sheet “Household Water System Management”, points out that these are classic signs of a system where daily supply is adequate but peak demand is not. The well is being treated like a city main when it behaves more like a slow spring.

Storage does not create new water. It creates room to collect what the well can already provide without strain and then release it at the speed the household actually lives at.

What A Storage Tank Really Does

A storage tank is often confused with a larger pressure tank. The roles are different. A pressure tank stores pressure, whereas a storage tank stores actual volume.

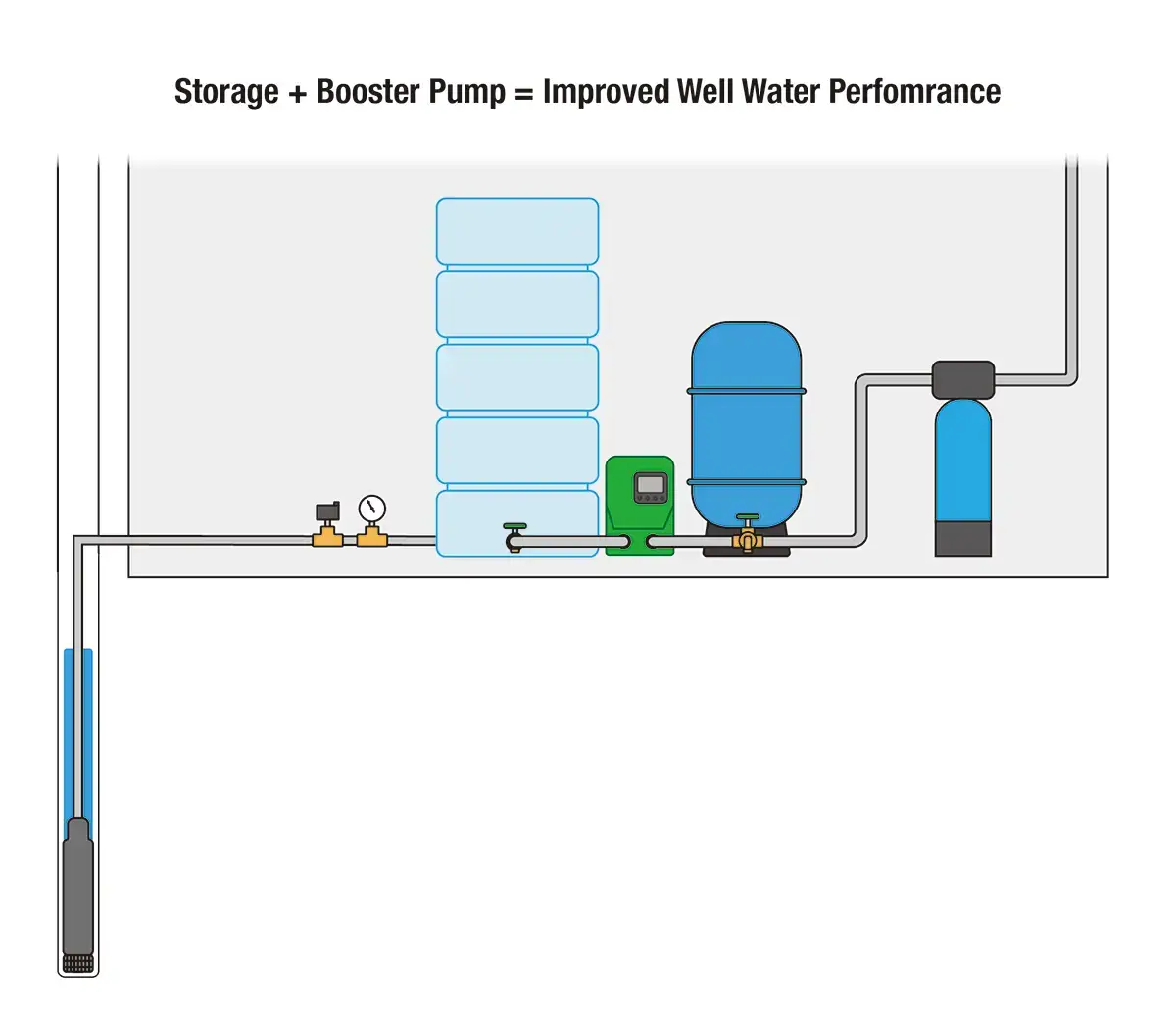

In a typical intermediate storage system, the well pump fills a non-pressurized tank at a rate that matches the well’s sustainable yield. A separate pump draws from that tank and sends water to the pressure tank and the rest of the home. Penn State Extension explains in “Household Water System Management” that this two-pump layout allows the well pump to run at a gentle, steady rate, rather than trying to chase every shower and appliance in real-time.

Nebraska Extension, in “Water Systems Planning for Rural Domestic Wells,” adds that when a well supplies enough water over a full day but not during peak hours, intermediate storage should be sized to carry at least a couple of hours of heavy household use.

In practice, this means the well can pump quietly in the background while the family uses the stored reserve during the busy parts of the day.

How Big the Storage Tank Should Be

Sizing storage is about matching three things. You need to understand how much water the well can truly produce, how much the household uses in a day, and how intense the peak periods are.

Penn State Extension suggests in “Household Water System Management” that a reasonable starting point is approximately 100 gallons of storage per person in the home. However, details depend on the plumbing and household habits.

The New York State Department of Health offers more specific ranges in “Individual Water Supply Wells.” For typical homes, they recommend the following:

- Wells producing three to five gallons per minute often pair well with about 100 to 250 gallons of storage.

- Wells producing one to three gallons per minute often need about 150 to 300 gallons of storage.

Some counties put those numbers directly into their codes. The Westchester County Department of Health, in its “Guidelines for Residential Wells and Water Storage,” requires that a four-gallon-per-minute well have at least 100 gallons of storage, a three-gallon-per-minute well have 200 gallons, and a two-gallon-per-minute well have 300 gallons. Wells below roughly two gallons per minute are flagged as difficult to support for full-time use, even with storage.

The Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation notes in “Water Well Drilling for the Prospective Well Owner” that average domestic use often falls between 200 and 400 gallons per day, and lenders commonly look for wells that produce around five gallons per minute. The same guide acknowledges that smaller yields can be effective when combined with suitable storage.

All of these numbers point toward the same idea. Storage should reflect both the steady output of the well and the way your home actually uses water during its busiest hours.

How Storage Connects To Pressure, Not Just Supply

Most people do not talk about gallons per minute. They talk about how the water feels.

A low-yield well often shows up as low water pressure, especially when several fixtures are running simultaneously. The shower collapses as soon as the washing machine starts. The kitchen sink fades whenever someone flushes a toilet. The issue is that the well cannot deliver water quickly enough to maintain steady pressure.

Storage on its own does not create strong pressure. It makes the conditions for it. In most designs, a storage tank is paired with a dedicated water pressure booster that pulls from the stored reserve and maintains consistent pressure through the house. Instead of riding directly on whatever the well pump can supply in that moment, the home draws from a stable pool that has already been collected.

The well controls the amount of water that enters the system in a day. The booster and pressure tank control how that water feels at the tap. When the two are matched properly, a well that would otherwise feel marginal can deliver steady, comfortable pressure all day.

When Storage Alone Cannot Fix the Problem

Storage is powerful, but it has limits. Some wells produce so little water that even a large tank cannot keep up with the demands of a modern home.

New York State Department of Health warns in “Individual Water Supply Wells” that wells producing less than about half a gallon per minute are rarely adequate for full-time residential use, even when storage is added. Westchester County’s rules reach a similar conclusion for wells under roughly two gallons per minute.

The Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation notes that while smaller yields can be managed with careful planning, there are instances where deepening the existing well or developing a new source becomes more realistic than relying on storage to bridge an ever-widening gap.

Storage works best for the large group of wells that can easily provide a day’s worth of water, yet cannot keep up with the sharp peaks that family life creates.

Maintenance And Water Quality With Storage

Adding storage changes how water moves through the system and creates new surfaces where water can rest. Those changes are manageable as long as the tank and pumps are treated as active components of the system, rather than forgotten hardware.

The Arizona Cooperative Extension, in “Water Storage Tank Disinfection, Testing, and Maintenance,” stresses that storage tanks used for drinking water should be constructed from materials rated for potable use, sealed to prevent the entry of insects and debris, and cleaned on a regular schedule to prevent biofilm and bacterial growth.

The Ohio Administrative Code, interpreted in conjunction with the Ohio Department of Health guidance on private water systems, permits plastic or fiberglass tanks with a capacity of less than one thousand gallons to serve as low-yield reservoirs in basements or utility spaces, provided that proper backflow protection and access for inspection are implemented.

Because storage tanks are not pressurized, they do not replace the pressure tank. A well-designed system still utilizes a pressure tank and switch to prevent the rapid cycling of the booster. If either the well pump or the booster pump starts and stops in very short bursts or runs for long stretches without rest, it is a sign that settings or tank sizing need attention.

Storage works best when the homeowner understands that it requires occasional inspection and cleaning, just like a well.

Questions To Ask Before You Commit

Installing storage is a significant project, but it is often far less expensive and far more predictable than drilling another well. The decision often comes down to a few straightforward questions.

- What is the well’s sustained yield during normal and dry conditions?

- Do you regularly lose pressure or run out of water during busy times, even though the well seems fine at other hours?

- Is there accessible space for a tank and a water pressure booster in a basement, outbuilding, or protected outdoor enclosure?

- Do local health or building codes already recommend or require storage for wells in your yield range?

Nebraska Extension, in “Water Systems Planning for Rural Domestic Wells,” sums up the logic clearly. When a well can satisfy total daily use but cannot meet short bursts of demand, intermediate storage is often the most practical way to make that well workable without drilling deeper.

Those questions determine whether storage belongs in your system now or whether the priority should be addressing other issues first.

What A Storage Tank Really Buys You

A storage tank does not change the geology under your property. It changes the terms of the relationship between your well and your home.

With storage, the well works at the slow, steady pace the aquifer supports. The house draws from a reserve that is built quietly in the background. Morning routines stop feeling like a scheduling puzzle. Laundry and dishes can be done when you have time, instead of only when the opportunity arises. The system keeps track of gallons, so you don’t have to.

For many low-yield wells, that shift is enough to turn a fragile, easily stressed supply into one that feels solid again.

Works Cited

Arizona Cooperative Extension. “Water Storage Tank Disinfection, Testing, and Maintenance.” University of Arizona Cooperative Extension.

https://extension.arizona.edu

Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. “Water Well Drilling for the Prospective Well Owner.” Montana DNRC.

https://dnrc.mt.gov

Nebraska Extension. “Water Systems Planning for Rural Domestic Wells.” University of Nebraska Extension.

https://extension.unl.edu

New York State Department of Health. “Individual Water Supply Wells.” New York State Department of Health.

https://www.health.ny.gov

Ohio Administrative Code and Ohio Department of Health. Private water system and low-yield reservoir provisions for household wells.

https://odh.ohio.gov

Penn State Extension. “Household Water System Management.” Pennsylvania State University Extension.

https://extension.psu.edu

Westchester County Department of Health. “Guidelines for Residential Wells and Water Storage.” Westchester County Department of Health.

https://health.westchestergov.com

Related Reading

- Buying a Home with a Well Manager System: What Every Homebuyer Should Know

- The Importance of Annual Well Inspections

- What is the Best Water Pressure Booster for a Low-Yield Well?

- Do I Have a Low-Yield Well? How to Tell When Pressure Problems Are Really a Supply Issue

- Will a Booster Pump Damage My Well Pump?